George Whitefield in America

A Documentary Journey

George Whitefield (1714-1770) was a Church of England clergyman, evangelist, and leader of Calvinistic Methodism. This digital exhibition on the “Grand Itinerant” focuses on select writings of Whitefield writings held by the Pitts Theology Library that relate to his remarkable ministry in colonial America, with a particular emphasis on his sermons and Orphan House. Whitefield, along with the Wesley brothers, was one of the founders of the Methodist movement in Britain, and its pioneer in the late 1730s. His powerful itinerant preaching ministry, often performed in the open air, put him at the center of the transatlantic Evangelical Revival or Great Awakening. He was the movement’s most effective revival preacher. Whitefield devoted a considerable part of his life and ministry to America. First travelling to Georgia in 1738, he would cross the Atlantic thirteen times before, fittingly, dying on a colonial preaching tour in Newburyport, Massachusetts in 1770. In America, Whitefield became known for his dynamic preaching that drew huge crowds. Although he provoked much controversy, he gained celebrity status as one of the most well-known figures in colonial America. As these writings show, Whitefield had a home base in Georgia, where he established the Bethesda Orphan House, while maintaining an extensive itinerant ministry throughout the colonies.

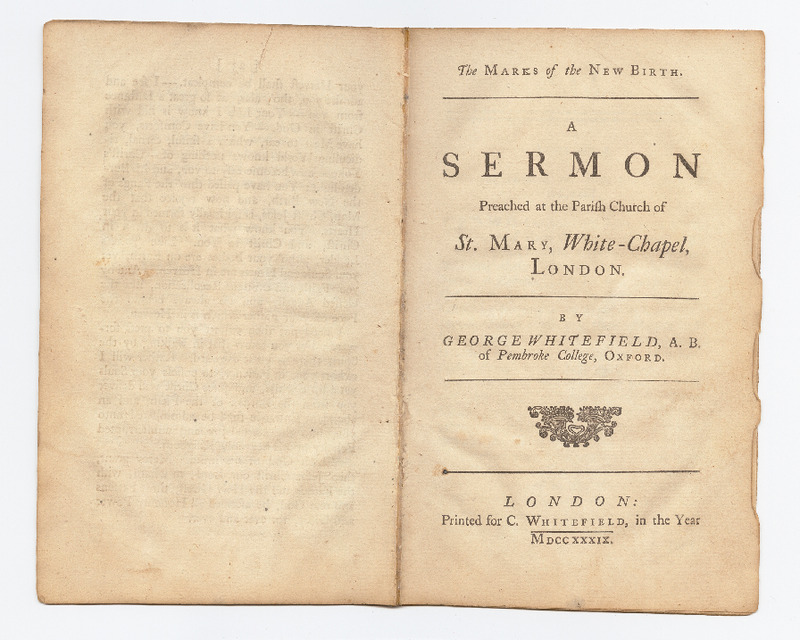

Around Easter 1735, three years prior to the evangelical conversions of the Wesley brothers, George Whitefield underwent a powerful experience of new birth. Subsequently, the message of transformative new birth in Christ was at the center of Whitefield’s evangelical preaching. By this, Whitefield meant a total inner conversion of the heart brought about by the supernatural work of the Holy Spirit, which would issue in a life marked by holiness. Utilizing his love of acting that gave him talent for dramatic preaching, one of Whitefield’s earliest published sermons is The Nature and Necessity of Our New Birth in Christ Jesus, in order to Salvation (London, 1737). This theme is continued in The Marks of the New Birth, which takes as its text Acts 19:5: “Have you received the Holy Ghost since ye believed?” Here, Whitefield presses the necessity of receiving the Holy Spirit in order to be a true Christian, the marks by which one can determine they have received the Spirit, and he then gives practical words of advice to people in different stages of their spiritual journeys.

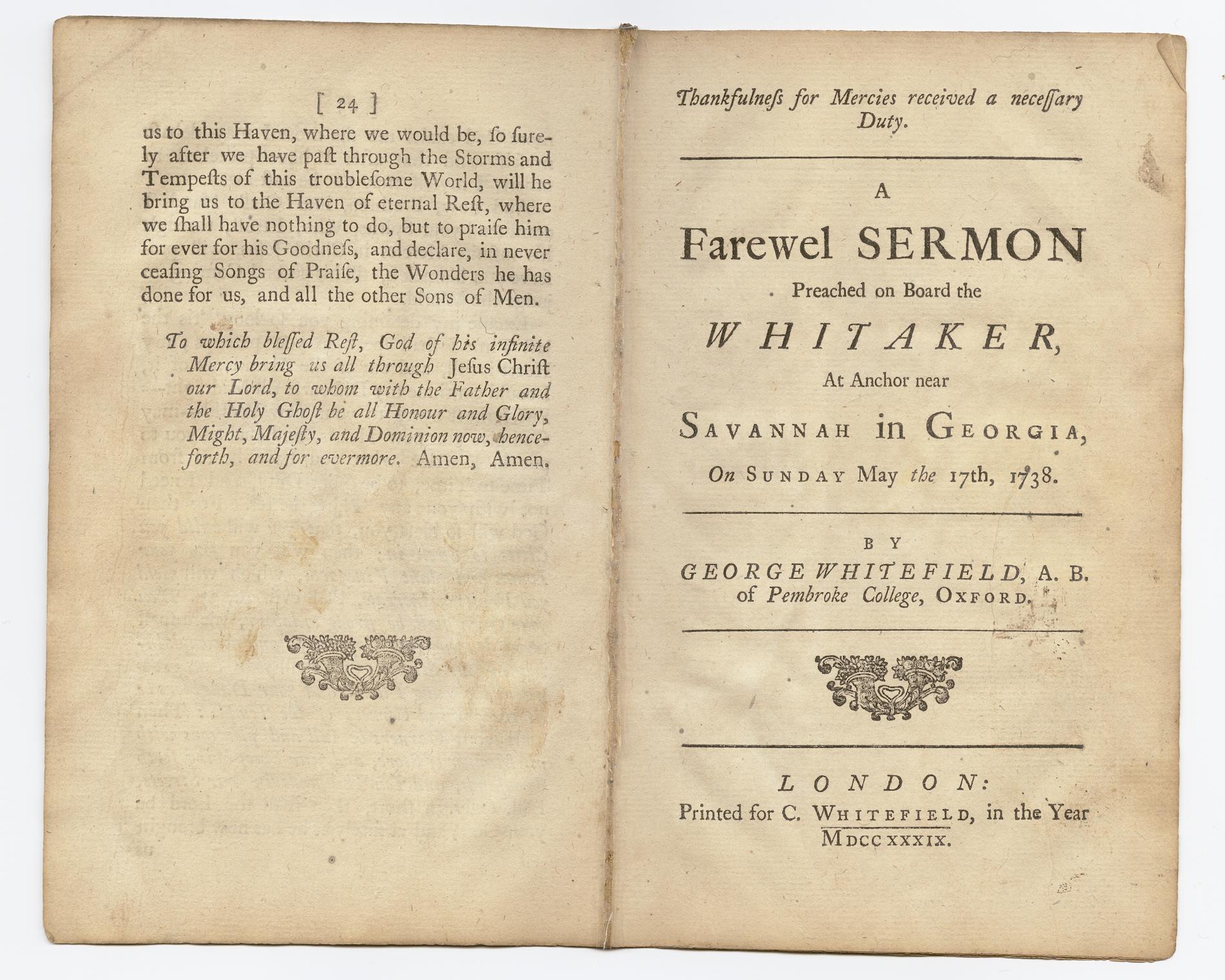

In February 1738, Whitefield set sail on the Whitaker en route to America on the first of his seven transatlantic voyages. Interestingly, on the coast of England, the ship passed the vessel in which John Wesley returned from the British colony of Georgia, where Whitefield was headed to take over and carry on Wesley’s ministry in Savannah. The Heinous Sin of Drunkenness provides us with an example of a sermon preached to a captive audience of passengers, crewmen, and soldiers, whom Whitefield treated as his parishioners. In this moralistic sermon (a common genre in the evangelical movement), aimed at promoting Christian conduct on the Whitaker, Whitefield laments that even some people who profess to be Christian have fallen into the sin of drunkenness. He goes on to give six reasons why drunkenness is incompatible with Christianity and argues that it imperils one’s salvation. Whitefield exhorts his hearers to turn away from the sin of drunkenness to a life of prayer and self-denial in which they labor “to be filled with the Spirit of God” (Eph. 5:6).

After nearly four months at sea on the Whitaker, anchored near Savannah, Georgia, Whitefield preached this farewell sermon to his shipmates, urging thankfulness to God for their safe arrival in the manner of Psalm 107:30-31: “Then they are glad, because they are at Rest, and so he bringeth them unto the Haven where they would be. O that Men would therefore praise the Lord for his Goodness, and declare the Wonders that he doeth for the Children of Men!” After lamenting the tendency of humanity toward the “Sin of Ingratitude,” Whitefield exhorts his fellow passengers to “give God your Hearts, your whole Hearts.” Continuing the moralistic theme of The Heinous Sin of Drunkenness, he then directly addresses, in turn, the soldiers, their wives, the sailors, military leaders, and Georgia settlers. The soldiers he urges to “Fear God, and you must honour the King” and the colonists should “Be Patters of Industry, as well as Piety.”

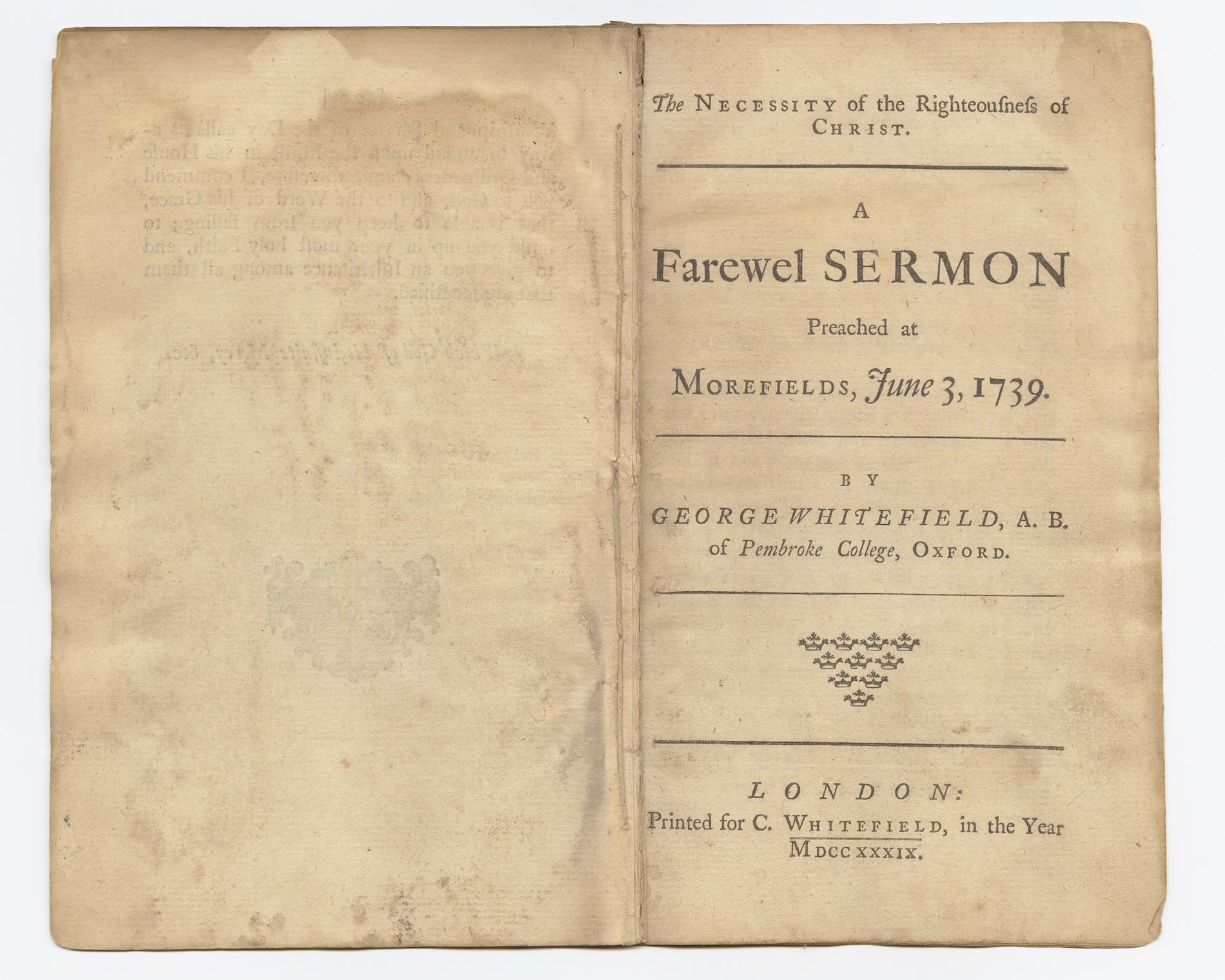

Following a short stay in Georgia, Whitefield returned to England to be ordained a priest and to raise funds for the establishment of an orphanage for needy children in Georgia. This is another farewell sermon, this time ahead of his second voyage to America, preached in Moorfields, London, where he had attracted large crowds as a charismatic revival preacher. In this strident evangelical sermon, Whitefield tells his hearers that they “cannot of themselves do any Thing acceptable to God” and salvation is “thro’ the unmerited Grace and Righteousness of our Lord Jesus Christ” alone. Whitefield’s audience is exhorted to believe in Christ like the Publican whom Jesus declared to be justified in Luke 18:14. Illustrating the evangelical emphasis on the atonement, Whitefield tells his listeners to “bathe yourselves in the Blood of our Lord Jesus Christ.” Another common evangelical theme present here is the conviction that true Christians will likely suffer for their faith and perhaps even be “laughed at and accounted methodically mad.” Whitefield notes that because of his impending transatlantic voyage, they may not see him again until judgement day, but they should nonetheless pray that God might grant that he returns to them. In turn, Whitefield will not forget them: “And when I am in the Midst of the Waves of the Sea, then shall my Prayer be, That you may all be found at the Right-Hand of the Son of God, and that you may increase with all the Increase of God.”

Here we have an example of a sermon preached in both America and Scotland. The title page notes that “The Substance of the following SERMON was delivered at the OldS. Church in Boston, Octob. 1740.” That is, it was preached near the peak of Whitefield’s popularity during his evangelistic tour of the Eastern seaboard. During his time in Boston, he attracted an estimated 20,000 hearers. In the year this sermon was published, he preached to a similar number in Cambuslang, just outside of Glasgow. This text of The Lord our Righteousness was preached in Glasgow in September 1741 and published in Boston the following year. The text of the sermon shows continuity with the soteriological focus of Whitefield’s sermons. It also illustrates that he had become an ardent Calvinist, equating Arminianism, legalism, and Catholicism with self-righteousness, something that would have resonated with his Reformed Bostonian and Scottish audiences.

In this letter, or thirty-two page short treatise dated August 31, 1742, from Cambuslang where the great Scottish awakening had been taking place, Whitefield demonstrates his desire to defend the American Great Awakening, even while on the other side of the Atlantic. Whitefield’s letter replies to an anonymous pamphlet that was critical of the revival in New England, questioning its authenticity and labelling it fanatical. His response is summed up in his contention “that the Work lately begun and carried out in New-England is not Enthusiasm and Delusion, but a great and marvellous Work of the Spirit of God.” To back up his argument, Whitefield provides extracts from the writings of several New England evangelical ministers.

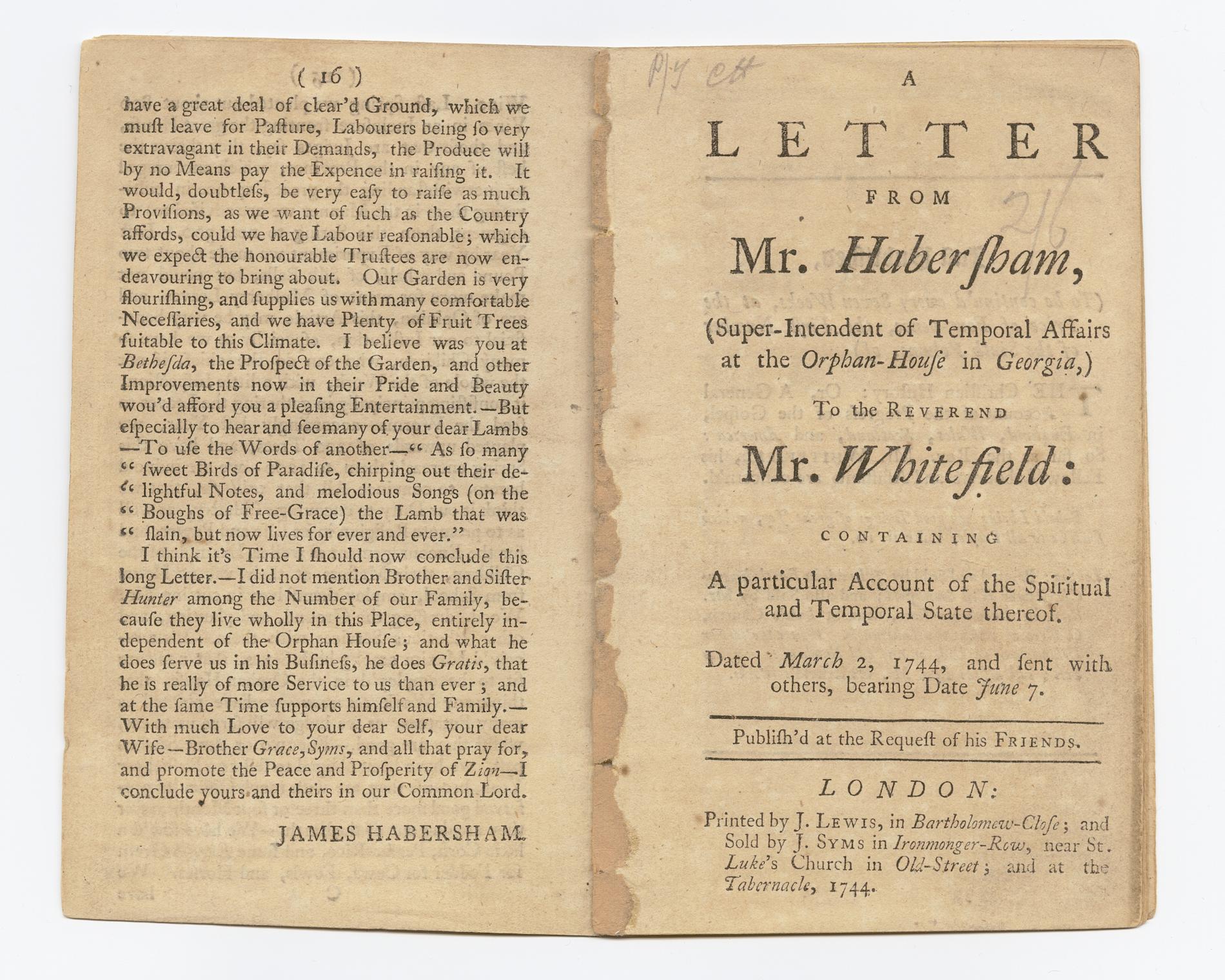

This sixteen-page pamphlet includes two 1744 letters from James Habersham to Whitefield relating to the Bethesda (house of mercy) Orphan House established in 1740 by Whitefield about ten miles from Savannah. Habersham, who later played a major role in the governance of colonial Georgia, was at the time “Superintendent of Temporal Affairs” at the Orphan House. As the subtitle of the pamphlet suggests, the letters provide details on the spiritual and temporal condition of the orphanage. Regarding spiritual matters, through letters of Jonathan Barber (superintendent of spiritual affairs) and his wife Mary, Habersham relays to Whitefield accounts of intense emotional revival at the Orphan House that resulted in many conversions. Habersham’s report on temporal affairs supplies interesting information about the state of Bethesda, at which he tells us 67 people were living, 49 of which were children. He recounts his struggles to provide the orphanage with necessary goods in a way that is intertwined with his spiritual concerns for himself and the Bethesda project. Details are given about specific individuals, as well as the efforts made to plant crops and fruit trees and create pasture for cows, horses, and fowls.

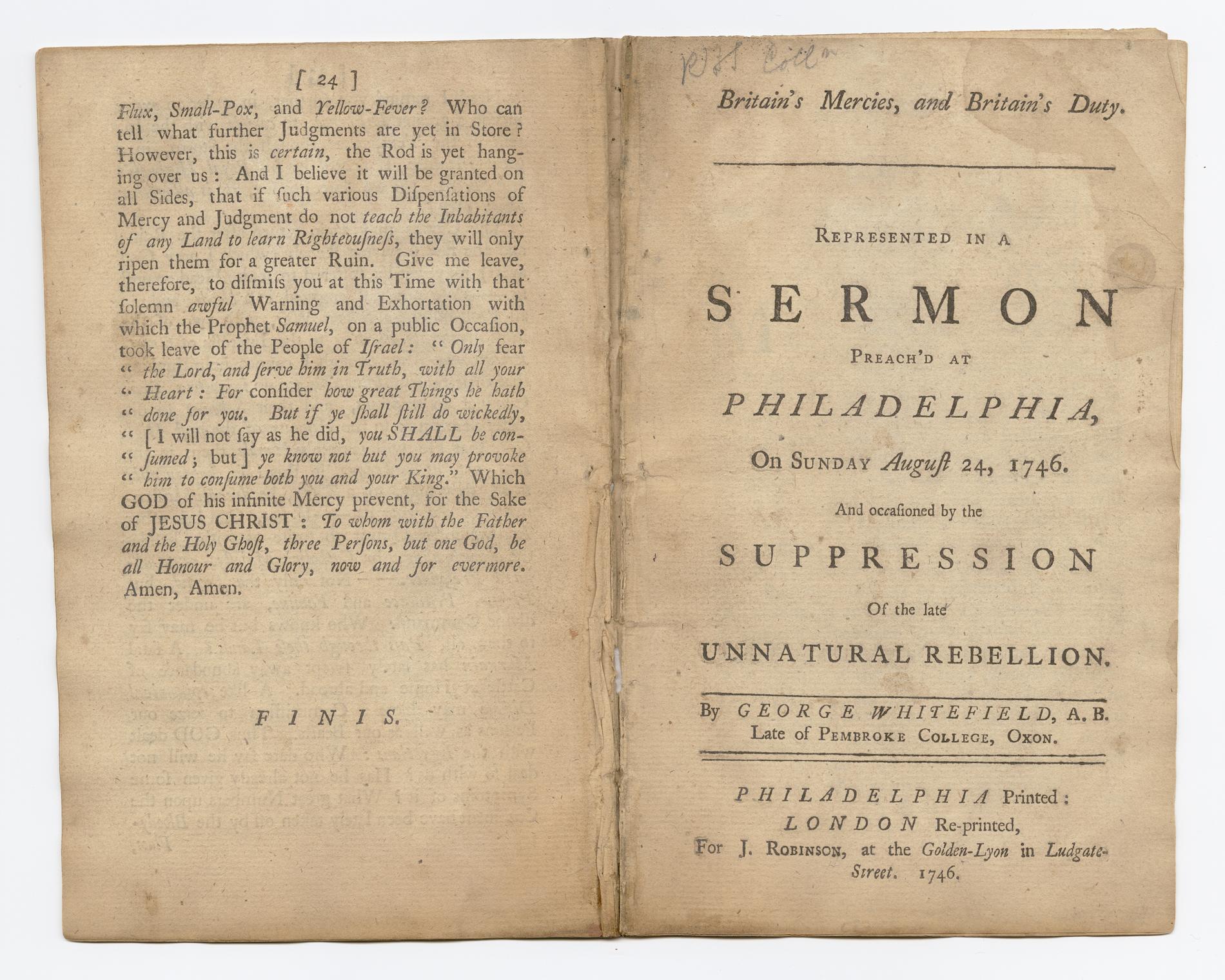

In Britain’s Mercies, and Britain’s Duty we have a political sermon by Whitefield displaying the British Protestant patriotism and anti-Catholicism that he shared with many evangelicals. The sermon was preached and published in Philadelphia (and reprinted in London) in the aftermath of the failure of the Jacobite rebellion, which attempted to restore the Catholic Stuart line to the British throne. Following the defeat of the uprising, Pennsylvania Governor George Thomas declared July 24, 1746, as a day of thanksgiving. Whitefield’s sermon was preached a month later to commemorate the “Suppression of the most horrid and unnatural Rebellion.” The sermon contrasts the fatherly benevolence of King George II and the liberty enjoyed by his British subjects with the “arbitrary and tyrannical” rule that would have ensued if the rebellion had succeeded. For Whitefield, “the horrid Plot, first hatched in Hell, and afterwards nursed at Rome” could have led to violent persecution and invading “Swarms of Monks, Dominicans and Friars” and Catholic bishops. In such a scenario, Whitefield rhetorically asked, “How soon would have our Pulpits have every where been filled with these old antichristian Doctrines, Free-will, Meriting by Works, Transubstantiation, Purgatory, Works of Super-errogation, Passive Obedience, Non-resistance, and all the other Abominations of the Whore of Babylon?”

Whitefield argued that because of the sins of the people in Britain and America, God could have justly allowed the rebellion to succeed, yet God was nonetheless merciful. Ultimately, it was God who was primarily responsible for the victory. Therefore, Britons, like the nation of Israel in the Old Testament, should rejoice in the Lord for his gift of undeserved mercy on the nation. To avoid calamity in the future, they must be obedient to God’s commands and turn to righteousness.

This manuscript letter from George Whitefield to Charles Wesley dated July 29, 1762, was posted from Norwich, England. It provides rare insight into Whitefield’s short itinerant ministry tour of Holland. Whitefield, who had just arrived back in England, reported on the “Divine Providence” that led him to Holland. At Rotterdam he preached to the English and “deep impressions were made by the word.” He also travelled to the Hague, Gouda, Haarlem, and Leiden, but noted that his inability to preach in Dutch was a hindrance: “How did I lament the confusion of tongues!” The experience of being again at sea led him to theological reflection and a desire to return again to America: “I hope death will be ready with His Packet-boat to carry me to glory – Oh that it may find me Itinerating! What say You to a Sea Voyage? I find the sea air very bracing – Blessed be God I have hopes now if I must live of taking another trip to America.”

The final section of volume three of A Select Collection of Letters contains materials relating to Whitefield’s ministry in Georgia, especially regarding the Bethesda Orphan House. This includes a series of nine letters exchanged with Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Secker (seven of which were written by Whitefield to Secker), in which Whitefield advocated for the conversion of Bethesda into a college of higher education (to be named Bethesda College). These letters followed on from Whitefield’s securing of support from Governor James Wright and both Houses of Assembly in Georgia. To further this endeavor, Whitefield sent a memorial to King George III requesting the grant of a royal charter to allow the project to commence. The memorial was passed on to Archbishop Secker, a long-time critic of Methodism, who declined to endorse the establishment of the college. The publication of the letters after the negotiations with Secker had failed (and in the year of Secker’s death), represent Whitefield’s attempt to positively portray his efforts to the public. Knowing that his financial and other support for the college project depended on both Anglicans and other Protestants, Whitefield refused to accede to Secker’s requested revisions to the charter that would have given it an unambiguously Anglican foundation.

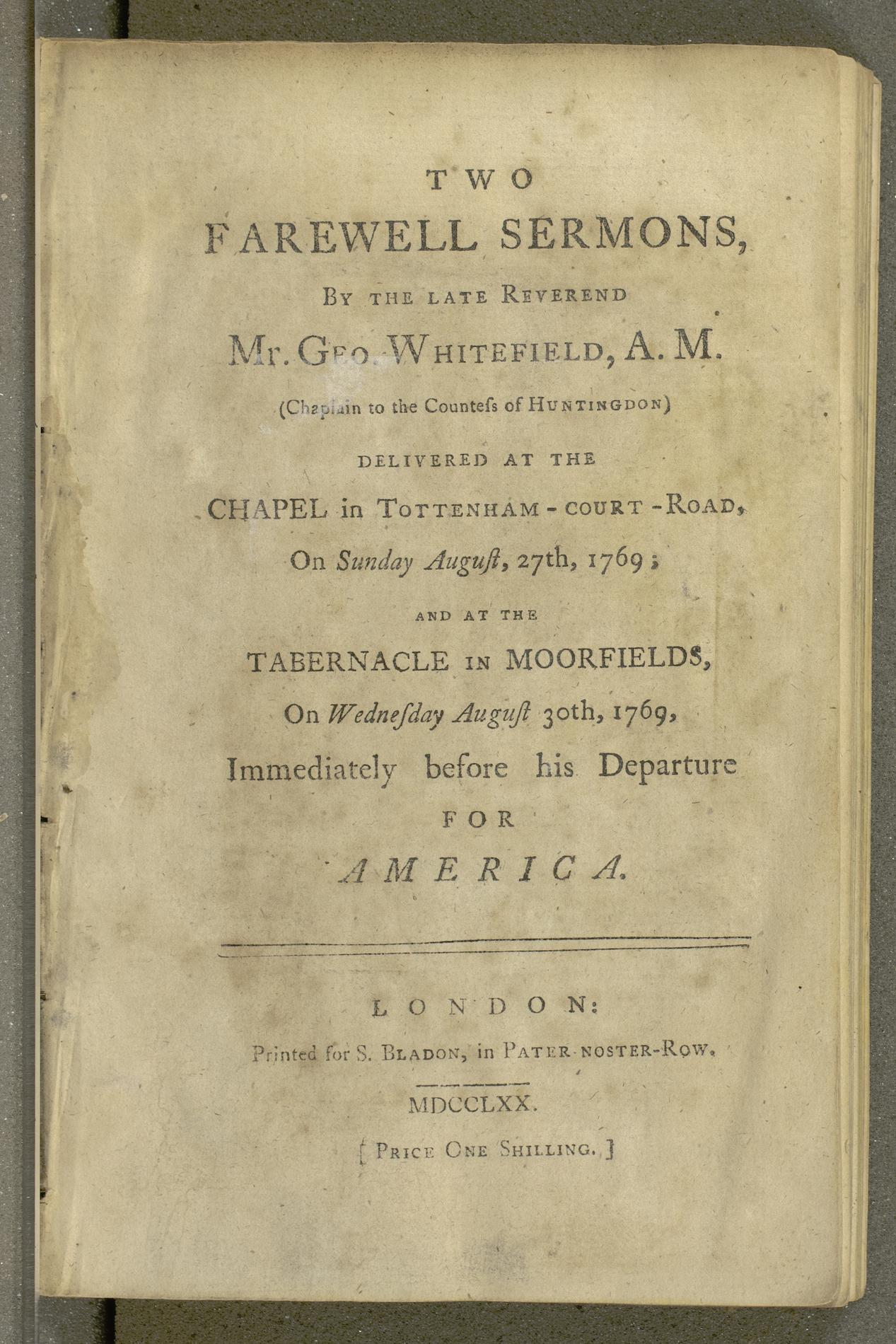

In August 1769, Whitefield preached Two Farewell Sermons in London before what proved to be his final journey to America. This edition of the sermons was published in November 1770, after word of his death had reached England. Illustrative of the direction many of his followers would go into Dissenting churches, George Burder, later a Congregationalist minister, arranged for the publication of the sermons. As the preface explains, the sermons were transcribed from Burder’s shorthand notes. In the first sermon, Whitefield included an illustration revealing of his now extensive experience of the American landscape. Reflecting on the long journey of the patriarch Jacob, he commented, “You who were born, and live in England, can have little idea of this; but those who travel in the American woods, often go hundreds of miles, covered with lofty trees, like the tall cedars of Lebanon” (12-13).

In both sermons, Whitefield stated that the primary purpose of his thirteenth transatlantic journey was to be present at the Orphan House on March 25, 1770, for the thirtieth anniversary of him laying the foundation stone of Bethesda so that he could dedicate the renovations and new buildings then being completed. Ruminating on his divine calling to America, Whitefield stated: “God called me to Georgia first, when I had all the churches in London open to me, when five or six constables were obliged to be placed at the doors to prevent the people from crouding [sic] too much; I might have settled in London, I was offered hundreds [of parish livings] then, yet I gave it all up to turn pilgrim for God, to go over into a foreign clime, out a love for immortal souls and I go, I hope, with that single intention now” (41).

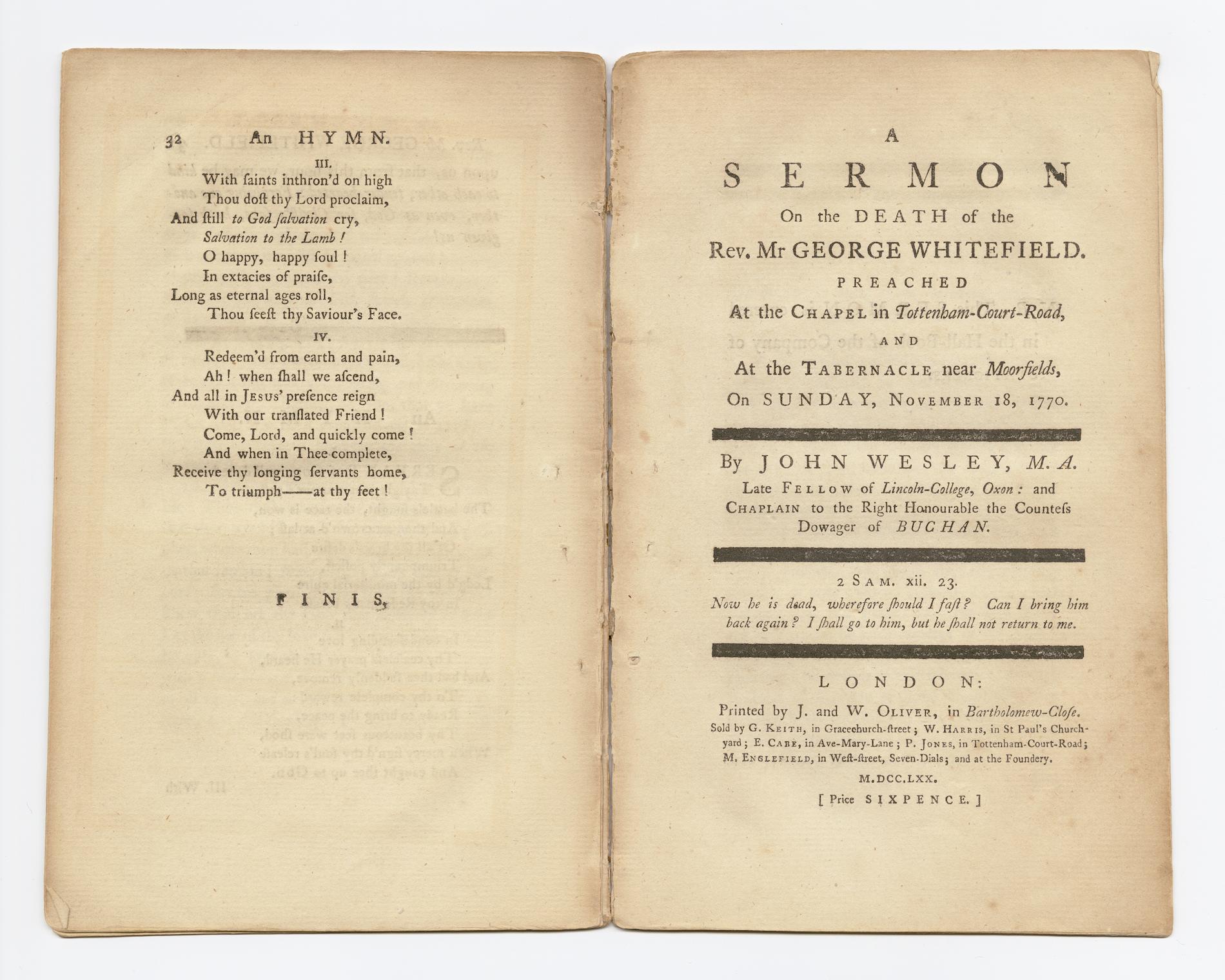

George Whitefield died at the age of 55 on September 30, 1770, in Newburyport, Massachusetts during his seventh tour of colonial America. He was buried in a crypt under the pulpit of Old South Presbyterian Church in Newburyport. Numerous sermons were preached and published in commemoration of the extraordinary life of the “Grand Itinerant.” According to Whitefield’s wishes, his long-time friend and fellow founder of Methodism, John Wesley, preached this funeral sermon at both of Whitefield’s London chapels. While Whitefield’s Calvinist colleagues understandably objected to Wesley’s omission of his Calvinism, it was nonetheless a heartfelt tribute to his dear friend and fellow evangelist. The sermon consists of three parts: (1) a brief biography; (2) an examination of Whitefield’s character; and (3) an exhortation to imitate his catholic spirit and keep close to his “grand doctrines” of the new birth and justification by faith. The biographical sketch, following Whitefield’s published journals, gives considerable attention and praise to his remarkable itinerant evangelism in America and his benevolent ministry with the Bethesda Orphan House in Georgia.